Mahendra, seven year old student in Nangi 2009

When I was in Nepal last September and October I interviewed Mahabir in Pokhara and Kathmandu. For those of you who know him well…it is difficult to get him to sit in one place for long. He was most gracious and patient with me as we sat for long hours of discussion. I had questions prepared over a chronological timeline but mostly he just talked and I took notes.

Over the last several months as I reviewed and organized my notes I find many detailed conversations but an assortment of cursory notes which I scribbled as I listened to some extraordinary stories. We covered as much as possible, yet there was so much I didn’t know enough to ask about. Mahabir has continued to support this project by answering in great detail my weekly questions as I whittle away at the specifics of his life, and lately his early teaching years. The following is an excerpt from one of those emails….he describes it so well, there seemed little I could improve on so I have copied his note to share directly:

Young student in Pokhara, Nepal 2009

“I taught in four high schools in Chitwan over a period of 13 years. I started teaching from Dibyanagar High School and taught there about a year. Then I was transferred to Nepal High School where I taught for about four years. From Nepal High School I was transferred to Birendranagar High School where I taught about a year. Then I was transferred to Khairahani High School…from where I had completed my 10th grade. The district education office transferred me wherever they needed me to fill in the post of science and math teacher. I was happy to go anywhere.”

“I was a good science and math teacher and the students liked me, wherever I went. Actually I had turned just 19 years when I started my teaching and the students I was teaching were like my friends. I treated the students as my friends in all the years of my teaching career and spent more time with the students than I did with my fellow teachers. I was strict teacher in the classroom and the students were afraid of me for being naughty, however, I was just like their friends outside classrooms.”

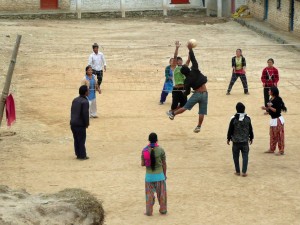

Himanchal Higher Education School students playing volleyball after school, Nangi 2009.

“I organized several programs with the students to raise money to build a good science lab. We did cultural programs during the festivals to raise money. We planted banana, ginger and turmeric in the field owned by the school and sold them. We raised pigs and built fish ponds in the school’s land. The science lab that we built in Khairahani High School was the best science lab in Chitwan and I taught students lots of practical sciences. Therefore the students were happy with me. I even published a Science Lab Practical Handbook for the students. I went to India to get the handbook printed.”

“In this way I spent most of my time in the school with the students doing different things and teaching in the schools. We worked even during the holidays. As told by some of my friends, some of the parents of Brahaman and Chhetri students were not happy with me. It was because Brahamans and Chhetris were not supposed to touch pigs because they were higher castes. However, I had made the Brahaman and Chhetri students to be involved in the pig farm, which they were doing happily. But the parents never complained directly (even if they were unhappy) for making their sons and daughters work in the pig farm.”

Last week I wrote about the challenges in educating the Nepali rural poor. Even then, Mahabir was a pioneer in methods to engage students, raise money and improve the education of his students. Have you ever had to raise money for your own projects? Share you story with our readers by leaving a comment. Join me next week for more of Mahabir’s stories of teaching in Chitwan.